$ Kudu: Storage for Fast Analytics on Fast Data

Todd Lipcon, David Alves, Dan Burkert, Jean-Daniel Cryans, Adar Dembo

Mike Percy, Silvius Rus, Dave Wang, Matteo Bertozzi, Colin Patrick McCabe

Andrew Wang

Cloudera, inc.

28 September 2015

$ Abstract

Kudu is an open source storage engine for structured data which supports low-latency random access together with efficient analytical access patterns. Kudu distributes data using horizontal partitioning and replicates each partition using Raft consensus, providing low mean-time-to-recovery and low tail latencies. Kudu is designed within the context of the Hadoop ecosystem and supports many modes of access via tools such as Cloudera Impala[20], Apache Spark[28], and MapReduce[17].

$ 1 Introduction

∗This document is a draft. Edits will be made and republished to the Kudu open source project web site on a rolling basis.

In recent years, explosive growth in the amount of data being generated and captured by enterprises has resulted in the rapid adoption of open source technology which is able to store massive data sets at scale and at low cost. In particular, the Hadoop ecosystem has become a focal point for such “big data” workloads, because many traditional open source database systems have lagged in offering a scalable alternative.

Structured storage in the Hadoop ecosystem has typically been achieved in two ways: for static data sets, data is typically stored on HDFS using binary data formats such as Apache Avro[1] or Apache Parquet[3]. However, neither HDFS nor these formats has any provision for updating individual records, or for efficient random access. Mutable data sets are typically stored in semi-structured stores such as Apache HBase[2] or Apache Cassandra[21]. These systems allow for low-latency record-level reads and writes, but lag far behind the static file formats in terms of sequential read throughput for applications such as SQL-based analytics or machine learning.

The gap between the analytic performance offered by static data sets on HDFS and the low-latency row-level random access capabilities of HBase and Cassandra has required practitioners to develop complex architectures when the need for both access patterns arises in a single application. In particular, many of Cloudera’s customers have developed data pipelines which involve streaming ingest and updates in HBase, followed by periodic jobs to export tables to Parquet for later analysis. Such architectures suffer several downsides:

- Application architects must write complex code to manage the flow and synchronization of data between the two systems.

- Operators must manage consistent backups, security policies, and monitoring across multiple distinct systems.

- The resulting architecture may exhibit significant lag between the arrival of new data into the HBase “staging area” and the time when the new data is available for analytics.

- In the real world, systems often need to accomodate latearriving data, corrections on past records, or privacyrelated deletions on data that has already been migrated to the immutable store. Achieving this may involve expensive rewriting and swapping of partitions and manual intervention.

Kudu is a new storage system designed and implemented from the ground up to fill this gap between high-throughput sequential-access storage systems such as HDFS[27] and lowlatency random-access systems such as HBase or Cassandra. While these existing systems continue to hold advantages in some situations, Kudu offers a “happy medium” alternative that can dramatically simplify the architecture of many common workloads. In particular, Kudu offers a simple API for row-level inserts, updates, and deletes, while providing table scans at throughputs similar to Parquet, a commonly-used columnar format for static data.

This paper introduces the architecture of Kudu. Section 2 describes the system from a user’s point of view, introducing the data model, APIs, and operator-visible constructs. Section 3 describes the architecture of Kudu, including how it partitions and replicates data across nodes, recovers from faults, and performs common operations. Section 4 explains how Kudu stores its data on disk in order to combine fast random access with efficient analytics. Section 5 discusses integrations between Kudu and other Hadoop ecosystem projects. Section 6 presents preliminary performance results in synthetic workloads.

$ 2 Kudu at a high level

$ 2.1 Tables and schemas

From the perspective of a user, Kudu is a storage system for tables of structured data. A Kudu cluster may have any number of tables, each of which has a well-defined schema consisting of a finite number of columns. Each such column has a name, type (e.g INT32 or STRING) and optional nullability. Some ordered subset of those columns are specified to be the table’s primary key. The primary key enforces a uniqueness constraint (at most one row may have a given primary key tuple) and acts as the sole index by which rows may be efficiently updated or deleted. This data model is familiar to users of relational databases, but differs from many other distributed datastores such as Cassandra. MongoDB[6], Riak[8], BigTable[12], etc.

As with a relational database, the user must define the schema of a table at the time of creation. Attempts to insert data into undefined columns result in errors, as do violations of the primary key uniqueness constraint. The user may at any time issue an alter table command to add or drop columns, with the restriction that primary key columns cannot be dropped.

Our decision to explicitly specify types for columns instead of using a NoSQL-style “everything is bytes” is motivated by two factors:

- Explicit types allow us to use type-specific columnar encodings such as bit-packing for integers.

- Explicit types allow us to expose SQL-like metadata to other systems such as commonly used business intelligence or data exploration tools.

Unlike most relational databases, Kudu does not currently offer secondary indexes or uniqueness constraints other than the primary key. Currently, Kudu requires that every table has a primary key defined, though we anticipate that a future version will add automatic generation of surrogate keys.

$ 2.2 Write operations

After creating a table, the user mutates the table using Insert, Update, and Delete APIs. In all cases, the user must fully specify a primary key – predicate-based deletions or updates must be handled by a higher-level access mechanism (see section 5). Kudu offers APIs in Java and C++, with experimental support for Python. The APIs allow precise control over batching and asynchronous error handling to amortize the cost of round trips when performing bulk data operations (such as data loads or large updates). Currently, Kudu does not offer any multi-row transactional APIs: each mutation conceptually executes as its own transaction, despite being automatically batched with other mutations for better performance. Modifications within a single row are always executed atomically across columns.

$ 2.3 Read operations

Kudu offers only a Scan operation to retrieve data from a table. On a scan, the user may add any number of predicates to filter the results. Currently, we offer only two types of predicates: comparisons between a column and a constant value, and composite primary key ranges. These predicates are interpreted both by the client API and the server to efficiently cull the amount of data transferred from the disk and over the network.

In addition to applying predicates, the user may specify a projection for a scan. A projection consists of a subset of columns to be retrieved. Because Kudu’s on-disk storage is columnar, specifying such a subset can substantially improve performance for typical analytic workloads.

$ 2.4 Other APIs

In addition to data path APIs, the Kudu client library offers other useful functionality. In particular, the Hadoop ecosystem gains much of its performance by scheduling for data locality. Kudu provides APIs for callers to determine the mapping of data ranges to particular servers to aid distributed execution frameworks such as Spark, MapReduce, or Impala in scheduling.

$ 2.5 Consistency Model

1 In the current beta release of Kudu, this consistency support is not yet fully implemented. However, this paper describes the architecture and design of the system, despite the presence of some known consistency-related bugs.

Kudu provides clients the choice between two consistency modes. The default consistency mode is snapshot consistency. A scan is guaranteed to yield a snapshot with no anomalies in which causality would be violated1. As such, it also guarantees read-your-writes consistency from a single client.

By default, Kudu does not provide an external consistency guarantee. That is to say, if a client performs a write, then communicates with a different client via an external mechanism (e.g. a message bus) and the other performs a write, the causal dependence between the two writes is not captured. A third reader may see a snapshot which contains the second write without the first.

Based on our experiences supporting other systems such as HBase that also do not offer external consistency guarantees, this is sufficient for many use cases. However, for users who require a stronger guarantee, Kudu offers the option to manually propagate timestamps between clients: after performing a write, the user may ask the client library for a timestamp token. This token may be propagated to another client through the external channel, and passed to the Kudu API on the other side, thus preserving the causal relationship between writes made across the two clients.

If propagating tokens is too complex, Kudu optionally uses commit-wait as in Spanner[14]. After performing a write with commit-wait enabled, the client may be delayed for a period of time to ensure that any later write will be causally ordered correctly. Absent specialized time-keeping hardware, this can introduce significant latencies in writes (100-1000ms with default NTP configurations), so we anticipate that a minority of users will take advantage of this option. We also note that, since the publication of Spanner, several data stores have started to take advantage of real-time clocks. Given this, it is plausible that within a few years, cloud providers will offer tight global time synchronization as a differentiating service.

The assignment of operation timestamps is based on a clock algorithm termed HybridTime[15]. Please refer to the cited article for details.

$ 2.6 Timestamps

Although Kudu uses timestamps internally to implement concurrency control, Kudu does not allow the user to manually set the timestamp of a write operation. This differs from systems such as Cassandra and HBase, which treat the timestamp of a cell as a first-class part of the data model. In our experiences supporting users of these other systems, we have found that, while advanced users can make effective use of the timestamp dimension, the vast majority of users find this aspect of the data model confusing and a source of user error, especially with regard to the semantics of back-dated insertions and deletions.

We do, however, allow the user to specify a timestamp for a read operation. This allows the user to perform point-intime queries in the past, as well as to ensure that different distributed tasks that together make up a single “query” (e.g. as in Spark or Impala) read a consistent snapshot.

$ 3 Architecture

$ 3.1 Cluster roles

Following the design of BigTable and GFS[18] (and their open-source analogues HBase and HDFS), Kudu relies on a single Master server, responsible for metadata, and an arbitrary number of Tablet Servers, responsible for data. The master server can be replicated for fault tolerance, supporting very fast failover of all responsibilities in the event of an outage. Typically, all roles are deployed on commodity hardware, with no extra requirements for master nodes.

$ 3.2 Partitioning

As in most distributed database systems, tables in Kudu are horizontally partitioned. Kudu, like BigTable, calls these horizontal partitions tablets. Any row may be mapped to exactly one tablet based on the value of its primary key, thus ensuring that random access operations such as inserts or updates affect only a single tablet. For large tables where throughput is important, we recommend on the order of 10-100 tablets per machine. Each tablet can be tens of gigabytes.

Unlike BigTable, which offers only key-range-based partitioning, and unlike Cassandra, which is nearly always deployed with hash-based partitioning, Kudu supports a flexible array of partitioning schemes. When creating a table, the user specifies a partition schema for that table. The partition schema acts as a function which can map from a primary key tuple into a binary partition key. Each tablet covers a contiguous range of these partition keys. Thus, a client, when performing a read or write, can easily determine which tablet should hold the given key and route the request accordingly.

The partition schema is made up of zero or more hashpartitioning rules followed by an optional range-partitioning rule:

A hash-partitioning rule consists of a subset of the primary key columns and a number of buckets. For example, as expressed in our SQL dialect, DISTRIBUTE BY HASH(hostname, ts) INTO 16 BUCKETS. These rules convert tuples into binary keys by first concatenating the values of the specified columns, and then computing the hash code of the resulting string modulo the requested number of buckets. This resulting bucket number is encoded as a 32-bit big-endian integer in the resulting partition key.

A range-partitioning rule consists of an ordered subset of the primary key columns. This rule maps tuples into binary strings by concatenating the values of the specified columns using an order-preserving encoding.

By employing these partitioning rules, users can easily trade off between query parallelism and query concurrency based on their particular workload. For example, consider a time series application which stores rows of the form (host, metric, time, value) and in which inserts are almost always done with monotonically increasing time values. Choosing to hash-partition by timestamp optimally spreads the insert load across all servers; however, a query for a specific metric on a specific host during a short time range must scan all tablets, limiting concurrency. A user might instead choose to range-partition by timestamp while adding separate hash partitioning rules for the metric name and hostname, which would provide a good trade-off of parallelism on write and concurrency on read.

Though users must understand the concept of partitioning to optimally use Kudu, the details of partition key encoding are fully transparent to the user: encoded partition keys are not exposed in the API. Users always specify rows, partition split points, and key ranges using structured row objects or SQL tuple syntax. Although this flexibility in partitioning is relatively unique in the “NoSQL” space, it should be quite familiar to users and administrators of analytic MPP database management systems.

$ 3.3 Replication

2 Kudu gives administrators the option of considering a write-ahead log entry committed either after it has been written to the operating system buffer cache, or only after an explicit fsync operation has been performed. The latter provides durability even in the event of a full datacenter outage, but decreases write performance substantially on spinning hard disks.

In order to provide high availability and durability while running on large commodity clusters, Kudu replicates all of its table data across multiple machines. When creating a table, the user specifies a replication factor, typically 3 or 5, depending on the application’s availability SLAs. Kudu’s master strives to ensure that the requested number of replicas are maintained at all times (see Section 3.4.2).

Kudu employs the Raft[25] consensus algorithm to replicate its tablets. In particular, Kudu uses Raft to agree upon a logical log of operations (e.g. insert/update/delete) for each tablet. When a client wishes to perform a write, it first locates the leader replica (see Section 3.4.3) and sends a Write RPC to this replica. If the client’s information was stale and the replica is no longer the leader, it rejects the request, causing the client to invalidate and refresh its metadata cache and resend the request to the new leader. If the replica is in fact still acting as the leader, it employs a local lock manager to serialize the operation against other concurrent operations, picks an MVCC timestamp, and proposes the operation via Raft to its followers. If a majority of replicas accept the write and log it to their own local write-ahead logs^2^, the write is considered durably replicated and thus can be committed on all replicas. Note that there is no restriction that the leader must write an operation to its local log before it may be committed: this provides good latency-smoothing properties even if the leader’s disk is performing poorly.

In the case of a failure of a minority of replicas, the leader can continue to propose and commit operations to the tablet’s replicated log. If the leader itself fails, the Raft algorithm quickly elects a new leader. By default, Kudu uses a 500millisecond heartbeat interval and a 1500-millisecond election timeout; thus, after a leader fails, a new leader is typically elected within a few seconds.

Kudu implements some minor improvements on the Raft algorithm. In particular:

- As proposed in [19] we employ an exponential back-off algorithm after a failed leader election. We found that, as we typically commit Raft’s persistent metadata to contended hard disk drives, such an extension was necessary to ensure election convergence on busy clusters.

- When a new leader contacts a follower whose log diverges from its own, Raft proposes marching backward one operation at a time until discovering the point where they diverged. Kudu instead immediately jumps back to the last known committedIndex, which is always guaranteed to be present on any divergent follower. This minimizes the potential number of round trips at the cost of potentially sending redundant operations over the network. We found this simple to implement, and it ensures that divergent operations are aborted after a single round-trip.

Kudu does not replicate the on-disk storage of a tablet, but rather just its operation log. The physical storage of each replica of a tablet is fully decoupled. This yields several advantages:

- When one replica is undergoing physical-layer background operations such as flushes or compactions (see Section 4), it is unlikely that other nodes are operating on the same tablet at the same time. Because Raft may commit after an acknowledgment by a majority of replicas, this reduces the impact of such physical-layer operations on the tail latencies experienced by clients for writes. In the future, we anticipate implementing techniques such as the speculative read requests described in [16] to further decrease tail latencies for reads in concurrent read/write workloads.

- During development, we discovered some rare race conditions in the physical storage layer of the Kudu tablet. Because the storage layer is decoupled across replicas, none of these race conditions resulted in unrecoverable data loss: in all cases, we were able to detect that one replica had become corrupt (or silently diverged from the majority) and repair it.

$ 3.3.1 Configuration Change

Kudu implements Raft configuration change following the one-by-one algorithm proposed in [24]. In this approach, the number of voters in the Raft configuration may change by at most one in each configuration change. In order to grow a 3replica configuration to 5 replicas, two separate configuration changes (3→4, 4→5) must be proposed and committed.

Kudu implements the addition of new servers through a process called remote bootstrap. In our design, in order to add a new replica, we first add it as a new member in the Raft configuration, even before notifying the destination server that a new replica will be copied to it. When this configuration change has been committed, the current Raft leader replica triggers a StartRemoteBootstrap RPC, which causes the destination server to pull a snapshot of the tablet data and log from the current leader. When the transfer is complete, the new server opens the tablet following the same process as after a server restart. When the tablet has opened the tablet data and replayed any necessary write-ahead logs, it has fully replicated the state of the leader at the time it began the transfer, and may begin responding to Raft RPCs as a fully-functional replica.

In our current implementation, new servers are added immediately as VOTER replicas. This has the disadvantage that, after moving from a 3-server configuration to a 4-server configuration, three out of the four servers must acknowledge each operation. Because the new server is in the process of copying, it is unable to acknowledge operations. If another server were to crash during the snapshot-transfer process, the tablet would become unavailable for writes until the remote bootstrap finished.

To address this issue, we plan to implement a PRE VOTER replica state. In this state, the leader will send Raft updates and trigger remote bootstrap on the target replica, but not count it as a voter when calculating the size of the configuration’s majority. Upon detecting that the PRE VOTER replica has fully caught up to the current logs, the leader will automatically propose and commit another configuration change to transition the new replica to a full VOTER.

When removing replicas from a tablet, we follow a similar approach: the current Raft leader proposes an operation to change the configuration to one that does not include the node to be evicted. If this is committed, then the remaining nodes will no longer send messages to the evicted node, though the evicted node will not know that it has been removed. When the configuration change is committed, the remaining nodes report the configuration change to the Master, which is responsible for cleaning up the orphaned replica (see Section 3.4.2).

$ 3.4 The Kudu Master

Kudu’s central master process has several key responsibilities:

- Act as a catalog manager, keeping track of which tables and tablets exist, as well as their schemas, desired replication levels, and other metadata. When tables are created, altered, or deleted, the Master coordinates these actions across the tablets and ensures their eventual completion.

- Act as a cluster coordinator, keeping track of which servers in the cluster are alive and coordinating redistribution of data after server failures.

- Act as a tablet directory, keeping track of which tablet servers are hosting replicas of each tablet.

We chose a centralized, replicated master design over a fully peer-to-peer design for simplicity of implementation, debugging, and operations.

$ 3.4.1 Catalog Manager

The master itself hosts a single-tablet table which is restricted from direct access by users. The master internally writes catalog information to this tablet, while keeping a full writethrough cache of the catalog in memory at all times. Given the large amounts of memory available on current commodity hardware, and the small amount of metadata stored per tablet, we do not anticipate this becoming a scalability issue in the near term. If scalability becomes an issue, moving to a paged cache implementation would be a straightforward evolution of the architecture.

The catalog table maintains a small amount of state for each table in the system. In particular, it keeps the current version of the table schema, the state of the table (creating, running, deleting, etc), and the set of tablets which comprise the table. The master services a request to create a table by first writing a table record to the catalog table indicating a CREATING state. Asynchronously, it selects tablet servers to host tablet replicas, creates the Master-side tablet metadata, and sends asynchronous requests to create the replicas on the tablet servers. If the replica creation fails or times out on a majority of replicas, the tablet can be safely deleted and a new tablet created with a new set of replicas. If the Master fails in the middle of this operation, the table record indicates that a roll-forward is necessary and the master can resume where it left off. A similar approach is used for other operations such as schema changes and deletion, where the Master ensures that the change is propagated to the relevant tablet servers before writing the new state to its own storage. In all cases, the messages from the Master to the tablet servers are designed to be idempotent, such that on a crash and restart, they can be safely resent.

Because the catalog table is itself persisted in a Kudu tablet, the Master supports using Raft to replicate its persistent state to backup master processes. Currently, the backup masters act only as Raft followers and do not serve client requests. Upon becoming elected leader by the Raft algorithm, a backup master scans its catalog table, loads its in-memory cache, and begins acting as an active master following the same process as a master restart.

$ 3.4.2 Cluster Coordination

Each of the tablet servers in a Kudu cluster is statically configured with a list of host names for the Kudu masters. Upon startup, the tablet servers register with the Masters and proceed to send tablet reports indicating the total set of tablets which they are hosting. The first such tablet report contains information about all tablets. All future tablet reports are incremental, only containing reports for tablets that have been newly created, deleted, or modified (e.g. processed a schema change or Raft configuration change).

A critical design point of Kudu is that, while the Master is the source of truth about catalog information, it is only an observer of the dynamic cluster state. The tablet servers themselves are always authoritative about the location of tablet replicas, the current Raft configuration, the current schema version of a tablet, etc. Because tablet replicas agree on all state changes via Raft, every such change can be mapped to a specific Raft operation index in which it was committed. This allows the Master to ensure that all tablet state updates are idempotent and resilient to transmission delays: the Master simply compares the Raft operation index of a tablet state update and discards it if the index is not newer than the Master’s current view of the world.

This design choice leaves much responsibility in the hands of the tablet servers themselves. For example, rather than detecting tablet server crashes from the Master, Kudu instead delegates that responsibility to the Raft LEADER replicas of any tablets with replicas on the crashed machine. The leader keeps track of the last time it successfully communicated with each follower, and if it has failed to communicate for a significant period of time, it declares the follower dead and proposes a Raft configuration change to evict the follower from the Raft configuration. When this configuration change is successfully committed, the remaining tablet servers will issue a tablet report to the Master to advise it of the decision made by the leader.

In order to regain the desired replication count for the tablet, the Master selects a tablet server to host a new replica based on its global view of the cluster. After selecting a server, the Master suggests a configuration change to the current leader replica for the tablet. However, the Master itself is powerless to change a tablet configuration – it must wait for the leader replica to propose and commit the configuration change operation, at which point the Master is notified of the configuration change’s success via a tablet report. If the Master’s suggestion failed (e.g. because the message was lost) it will stubbornly retry periodically until successful. Because these operations are tagged with the unique index of the degraded configuration, they are fully idempotent and conflictfree, even if the Master issues several conflicting suggestions, as might happen soon after a master fail-over.

The master responds similarly to extra replicas of tablets. If the Master receives a tablet report which indicates that a replica has been removed from a tablet configuration, it stubbornly sends DeleteTablet RPCs to the removed node until the RPC succeeds. To ensure eventual cleanup even in the case of a master crash, the Master also sends such RPCs in response to a tablet report which identifies that a tablet server is hosting a replica which is not in the newest committed Raft configuration.

$ 3.4.3 Tablet Directory

In order to efficiently perform read and write operations without intermediate network hops, clients query the Master for tablet location information. Clients are “thick” and maintain a local metadata cache which includes their most recent information about each tablet they have previously accessed, including the tablet’s partition key range and its Raft configuration. At any point in time, the client’s cache may be stale; if the client attempts to send a write to a server which is no longer the leader for a tablet, the server will reject the request. The client then contacts the Master to learn about the new leader. In the case that the client receives a network error communicating with its presumed leader, it follows the same strategy, assuming that the tablet has likely elected a new leader.

In the future, we plan to piggy-back the current Raft configuration on the error response if a client contacts a non-leader replica. This will prevent extra round-trips to the master after leader elections, since typically the followers will have up-to-date information.

Because the Master maintains all tablet partition range information in memory, it scales to a high number of requests per second, and responds with very low latency. In a 270node cluster running a benchmark workload with thousands of tablets, we measured the 99.99th percentile latency of tablet location lookup RPCs at 3.2ms, with the 95th percentile at 374 microseconds and 75th percentile at 91 microseconds. Thus, we do not anticipate that the tablet directory lookups will become a scalability bottleneck at current target cluster sizes. If they do become a bottleneck, we note that it is always safe to serve stale location information, and thus this portion of the Master can be trivially partitioned and replicated across any number of machines.

$ 4 Tablet storage

Within a tablet server, each tablet replica operates as an entirely separate entity, significantly decoupled from the partitioning and replication systems described in sections 3.2 and 3.3. During development of Kudu, we found that it was convenient to develop the storage layer somewhat independently from the higher-level distributed system, and in fact many of our functional and unit tests operate entirely within the confines of the tablet implementation.

Due to this decoupling, we are exploring the idea of providing the ability to select an underlying storage layout on a per-table, per-tablet or even per-replica basis – a distributed analogue of Fractured Mirrors, as proposed in [26]. However, we currently offer only a single storage layout, described in this section.

$ 4.1 Overview

The implementation of tablet storage in Kudu addresses several goals:

Fast columnar scans In order to provide analytic performance comparable to best-of-breed immutable data formats such as Parquet and ORCFile[7], it’s critical that the majority of scans can be serviced from efficiently encoded columnar data files.

Low-latency random updates In order to provide fast access to update or read arbitrary rows, we require O(lg n) lookup complexity for random access.

Consistency of performance Based on our experiences supporting other data storage systems, we have found that users are willing to trade off peak performance in order to achieve predictability.

In order to provide these characteristics simultaneously, Kudu does not reuse any pre-existing storage engine, but rather chooses to implement a new hybrid columnar store architecture.

$ 4.2 RowSets

Tablets in Kudu are themselves subdivided into smaller units called RowSets. Some RowSets exist in memory only, termed MemRowSets, while others exist in a combination of disk and memory, termed DiskRowSets. Any given live (not deleted) row exists in exactly one RowSet; thus, RowSets form disjoint sets of rows. However, note that the primary key intervals of different RowSets may intersect.

At any point in time, a tablet has a single MemRowSet which stores all recently-inserted rows. Because these stores are entirely in-memory, a background thread periodically flushes MemRowSets to disk. The scheduling of these flushes is described in further detail in Section 4.11.

When a MemRowSet has been selected to be flushed, a new, empty MemRowSet is swapped in to replace it. The previous MemRowSet is written to disk, and becomes one or more DiskRowSets. This flush process is fully concurrent: readers can continue to access the old MemRowSet while it is being flushed, and updates and deletes of rows in the flushing MemRowSet are carefully tracked and rolled forward into the on-disk data upon completion of the flush process.

$ 4.3 MemRowSet Implementation

MemRowSets are implemented by an in-memory concurrent B-tree with optimistic locking, broadly based off the design of MassTree[22], with the following changes:

- We do not support removal of elements from the tree. Instead, we use MVCC records to represent deletions.

MemRowSets eventually flush to other storage, so we can defer removal of these records to other parts of the system.

Similarly, we do not support arbitrary in-place updates of records in the tree. Instead, we allow only modifications which do not change the value’s size: this permits atomic compare-and-swap operations to append mutations to a per-record linked list.

We link together leaf nodes with a next pointer, as in the B+-tree[13]. This improves our sequential scan performance, a critical operation.

We do not implement the full “trie of trees”, but rather just a single tree, since we are less concerned about extremely high random access throughput compared to the original application.

In order to optimize for scan performance over random access, we use slightly larger internal and leaf nodes sized at four cache-lines (256 bytes) each.

Unlike most data in Kudu, MemRowSets store rows in a row-wise layout. This still provides acceptable performance, since the data is always in memory. To maximize throughput despite the choice of row storage, we utilize SSE2 memory prefetch instructions to prefetch one leaf node ahead of our scanner, and JIT-compile record projection operations using LLVM[5]. These optimizations provide significant performance boosts relative to the naive implementation.

In order to form the key for insertion into the B-tree, we encode each row’s primary key using an order-preserving encoding as described in Section 3.2. This allows efficient tree traversal using only memcmp operations for comparison, and the sorted nature of the MemRowSet allows for efficient scans over primary key ranges or individual key lookups.

$ 4.4 DiskRowSet Implementation

When MemRowSets flush to disk, they become DiskRowSets. While flushing a MemRowSet, we roll the DiskRowSet after each 32 MB of IO. This ensures that no DiskRowSet is too large, thus allowing efficient incremental compaction as described later in Section 4.10. Because a MemRowSet is in sorted order, the flushed DiskRowSets will themselves also be in sorted order, and each rolled segment will have a disjoint interval of primary keys.

A DiskRowSet is made up of two main components: base data and delta stores. The base data is a column-organized representation of the rows in the DiskRowSet. Each column is separately written to disk in a single contiguous block of data. The column itself is subdivided into small pages to allow for granular random reads, and an embedded B-tree index allows efficient seeking to each page based on its ordinal offset within the rowset. Column pages are encoded using a variety of encodings, such as dictionary encoding, bitshuffle[23], or front coding, and is optionally compressed using generic binary compression schemes such as LZ4, gzip, or bzip2. These encodings and compression options may be specified explicitly by the user on a per-column basis, for example to designate that a large infrequently-accessed text column should be gzipped, while a column that typically stores small integers should be bit-packed. Several of the page formats supported by Kudu are common with those supported by Parquet, and our implementation shares much code with Impala’s Parquet library.

In addition to flushing columns for each of the user-specified columns in the table, we also write a primary key index column, which stores the encoded primary key for each row. We also flush a chunked Bloom filter[10] which can be used to test for the possible presence of a row based on its encoded primary key.

Because columnar encodings are difficult to update in place, the columns within the base data are considered immutable once flushed. Instead, updates and deletes are tracked through structures termed delta stores. Delta stores are either in-memory DeltaMemStores, or on-disk DeltaFiles. A DeltaMemStore is a concurrent B-tree which shares the implementation described above. A DeltaFile is a binary-typed column block. In both cases, delta stores maintain a mapping from (row offset, timestamp) tuples to RowChangeList records. The row offset is simply the ordinal index of a row within the RowSet – for example, the row with the lowest primary key has offset 0. The timestamp is the MVCC timestamp assigned when the operation was originally written. The RowChangeList is a binary-encoded list of changes to a row, for example indicating SET column id 3 = ‘foo’ or DELETE.

When servicing an update to data within a DiskRowSet, we first consult the primary key index column. By using its embedded B-tree index, we can efficiently seek to the page containing the target row. Using page-level metadata, we can determine the row offset for the first cell within that page. By searching within the page (eg via in-memory binary search) we can then calculate the target row’s offset within the entire DiskRowSet. Upon determining this offset, we insert a new delta record into the rowset’s DeltaMemStore.

$ 4.5 Delta Flushes

Because the DeltaMemStore is an in-memory store, it has finite capacity. The same background process which schedules flushes of MemRowSets also schedules flushes of DeltaMemStores. When flushing a DeltaMemStore, a new empty store is swapped in while the existing one is written to disk and becomes a DeltaFile. A DeltaFile is a simple binary column which contains an immutable copy of the data that was previously in memory.

$ 4.6 INSERT path

As described previously, each tablet has a single MemRowSet which is holds recently inserted data; however, it is not sufficient to simply write all inserts directly to the current MemRowSet, since Kudu enforces a primary key uniqueness constraint. In other words, unlike many NoSQL stores, Kudu differentiates INSERT from UPSERT.

In order to enforce the uniqueness constraint, Kudu must consult all of the existing DiskRowSets before inserting the new row. Because there may be hundreds or thousands of DiskRowSets per tablet, it is important that this be done efficiently, both by culling the number of DiskRowSets to consult and by making the lookup within a DiskRowSet efficient.

In order to cull the set of DiskRowSets to consult on an INSERT operation, each DiskRowSet stores a Bloom filter of the set of keys present. Because new keys are never inserted into an existing DiskRowSet, this Bloom filter is static data. We chunk the Bloom filter into 4KB pages, each corresponding to a small range of keys, and index those pages using an immutable B-tree structure. These pages as well as their index are cached in a server-wide LRU page cache, ensuring that most Bloom filter accesses do not require a physical disk seek.

Additionally, for each DiskRowSet, we store the minimum and maximum primary key, and use these key bounds to index the DiskRowSets in an interval tree. This further culls the set of DiskRowSets to consult on any given key lookup. A background compaction process, described in Section 4.10 reorganizes DiskRowSets to improve the effectiveness of the interval tree-based culling.

For any DiskRowSets that are not able to be culled, we must fall back to looking up the key to be inserted within its encoded primary key column. This is done via the embedded B-tree index in that column, which ensures a logarithmic number of disk seeks in the worst case. Again, this data access is performed through the page cache, ensuring that for hot areas of key space, no physical disk seeks are needed.

$ 4.7 Read path

Similar to systems like X100[11], Kudu’s read path always operates in batches of rows in order to amortize function call cost and provide better opportunities for loop unrolling and SIMD instructions. Kudu’s in-memory batch format consists of a top-level structure which contains pointers to smaller blocks for each column being read. Thus, the batch itself is columnar in memory, which avoids any offset calculation cost when copying from columnar on-disk stores into the batch.

When reading data from a DiskRowSet, Kudu first determines if a range predicate on the scan can be used to cull the range of rows within this DiskRowSet. For example, if the scan has set a primary key lower bound, we perform a seek within the primary key column in order to determine a lower bound row offset; we do the same with any upper bound key. This converts the key range predicate into a row offset range predicate, which is simpler to satisfy as it requires no expensive string comparisons.

Next, Kudu performs the scan one column at a time. First, it seeks the target column to the correct row offset (0, if no predicate was provided, or the start row, if it previously determined a lower bound). Next, it copies cells from the source column into our row batch using the page-encoding specific decoder. Last, it consult the delta stores to see if any later updates have replaced cells with newer versions, based on the current scan’s MVCC snapshot, applying those changes to our in-memory batch as necessary. Because deltas are stored based on numerical row offsets rather than primary keys, this delta application process is extremely efficient: it does not require any per-row branching or expensive string comparisons.

After performing this process for each row in the projection, it returns the batch results, which will likely be copied into an RPC response and sent back to the client. The tablet server maintains stateful iterators on the server side for each scanner so that successive requests do not need to re-seek, but rather can continue from the previous point in each column file.

$ 4.8 Lazy Materialization

If predicates have been specified for the scanner, we perform lazy materialization[9] of column data. In particular, we prefer to read columns which have associated range predicates before reading any other columns. After reading each such column, we evaluate the associated predicate. In the case that the predicate filters all rows in this batch, we short circuit the reading of other columns. This provides a significant speed boost when applying selective predicates, as the majority of data from the other selected columns will never be read from disk.

$ 4.9 Delta Compaction

Because deltas are not stored in a columnar format, the scan speed of a tablet will degrade as ever more deltas are applied to the base data. Thus, Kudu’s background maintenance manager periodically scans DiskRowSets to find any cases where a large number of deltas (as identified by the ratio between base data row count and delta count) have accumulated, and schedules a delta compaction operation which merges those deltas back into the base data columns.

In particular, the delta compaction operation identifies the common case where the majority of deltas only apply to a subset of columns: for example, it is common for a SQL batch operation to update just one column out of a wide table. In this case, the delta compaction will only rewrite that single column, avoiding IO on the other unmodified columns.

$ 4.10 RowSet Compaction

In addition to compacting deltas into base data, Kudu also periodically compacts different DiskRowSets together in a process called RowSet compaction. This process performs a keybased merge of two or more DiskRowSets, resulting in a sorted stream of output rows. The output is written back to new DiskRowSets, again rolling every 32 MB, to ensure that no DiskRowSet in the system is too large.

RowSet compaction has two goals:

- We take this opportunity to remove deleted rows.

- This process reduces the number of DiskRowSets that overlap in key range. By reducing the amount by which RowSets overlap, we reduce the number of RowSets which are expected to contain a randomly selected key in the tablet. This value acts as an upper bound for the number of Bloom filter lookups, and thus disk seeks, expected to service a write operation within the tablet.

$ 4.11 Scheduling maintenance

As described in the sections above, Kudu has several different background maintenance operations that it performs to reduce memory usage and improve performance of the on-disk layout. These operations are performed by a pool of maintenance threads that run within the tablet server process. Toward the design goal of consistent performance, these threads run all the time, rather than being triggered by specific events or conditions. Upon the completion of one maintenance operation, a scheduler process evaluates the state of the on-disk storage and picks the next operation to perform based on a set of heuristics meant to balance memory usage, write-ahead log retention, and the performance of future read and write operations.

In order to select DiskRowSets to compact, the maintenance scheduler solves an optimization problem: given an IO budget (typically 128 MB), select a set of DiskRowSets such that compacting them would reduce the expected number of seeks, as described above. This optimization turns out to be a series of instances of the well-known integer knapsack problem, and is able to be solved efficiently in a few milliseconds.

Because the maintenance threads are always running small units of work, the operations can react quickly to changes in workload behavior. For example, when insertion workload increases, the scheduler quickly reacts and flushes in-memory stores to disk. When the insertion workload reduces, the server performs compactions in the background to increase performance for future writes. This provides smooth transitions in performance, making it easier for developers and operators to perform capacity planning and estimate the latency profile of their workloads.

$ 5 Hadoop Integration

$ 5.1 MapReduce and Spark

Kudu was built in the context of the Hadoop ecosystem, and we have prioritized several key integrations with other Hadoop components. In particular, we provide bindings for MapReduce jobs to either input or output data to Kudu tables. These bindings can be easily used in Spark[28] as well. A small glue layer binds Kudu tables to higher-level Spark concepts such as DataFrames and Spark SQL tables.

These bindings offer native support for several key features:

- Locality internally, the input format queries the Kudu master process to determine the current locations for each tablet, allowing for data-local processing.

- Columnar Projection the input format provides a simple API allowing the user to select which columns are required for their job, thus minimizing the amount of IO required.

- Predicate pushdown the input format offers a simple API to specify predicates which will be evaluated serverside before rows are passed to the job. This predicate push-down increases performance and can be easily accessed through higher-level interfaces such as SparkSQL.

$ 5.2 Impala

Kudu is also deeply integrated with Cloudera Impala[20]. In fact, Kudu provides no shell or SQL parser of its own: the only support for SQL operations is via its integration with Impala. The Impala integration includes several key features:

Locality the Impala planner uses the Kudu Java API to inspect tablet location information and distributes backend query processing tasks to the same nodes which store the data. In typical queries, no data is transferred over the network from Kudu to Impala. We are currently investigating further optimizations based on shared memory transport to make the data transfer even more efficient.

Predicate pushdown support the Impala planner has been modified to identify predicates which are able to be pushed down to Kudu. In many cases, pushing a predicate allows significant reduction in IO, because Kudu lazily materializes columns only after predicates have been passed.

DDL extensions Impala’s DDL statements such as CREATE TABLE have been extended to support specifying Kudu partitioning schemas, replication factors, and primary key definitions.

DML extensions Because Kudu is the first mutable store in the Hadoop ecosystem that is suitable for fast analytics, Impala previously did not support mutation statements such as UPDATE and DELETE. These statements have been implemented for Kudu tables.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDFS | 4.1 | 10.4 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 17.5 | 3.5 | 12.7 | 31.5 |

| Kudu | 4.3 | 9.1 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 16.0 | 1.4 | 13.8 | 10.5 |

| Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | |

| HDFS | 49.7 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 8.5 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

| Kudu | 47.7 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 2.4 |

| Q17 | Q18 | Q19 | Q20 | Q21 | Q22 | Geomean | ||

| HDFS | 23.4 | 14.8 | 19.4 | 6.1 | 22.4 | 3.6 | 8.8 | |

| Kudu | 17.7 | 19.0 | 17.8 | 7.0 | 12.0 | 3.6 | 6.7 |

Table 1: TPC-H query times: Impala on Kudu vs Impala on Parquet/HDFS (seconds, lower is better)

Impala’s modular architecture allows a single query to transparently join data from multiple different storage components. For example, a text log file on HDFS can be joined against a large dimension table stored in Kudu.

$ 6 Performance evaluation

$ 6.1 Comparison with Parquet

To evaluate the performance of Kudu for analytic workloads, we loaded the industry-standard TPC-H data set at scale factor 100 on a cluster of 75 nodes, each with 64GB of memory, 12 spinning disks, and dual 6-core Xeon E5-2630L processors running at 2GHz. Because the total memory on the cluster is much larger than the data to be queried, all queries operate fully against cached data; however, all data is fully persisted in the columnar DiskRowSet storage of Kudu rather than being left in memory stores.

We used Impala 2.2 to run the full set of 22 TPC-H queries against the same data set stored in Parquet as well as on Kudu. For the Kudu tables, we hash-partitioned each table by its primary key into 256 buckets, with the exception of the very small nation and region dimension tables, which were stored in a single tablet each. All data was loaded using CREATE TABLE AS SELECT statements from within Impala.

While we have not yet performed an in-depth benchmark including concurrent workloads, we compared the wall time of each TPC-H query between the two systems. The results are summarized in Table 1. Across the set of queries, Kudu performed on average 31% faster than Parquet. We believe that Kudu’s performance advantage is due to two factors:

- Lazy materialization Several of the queries in TPCH include a restrictive predicate on larger tables such as lineitem. Kudu supports lazy materialization, avoiding IO and CPU costs on other columns in the cases where the predicate does not match. The current implementation of Parquet in Impala does not support this feature.

- CPU efficiency The Parquet reader in Impala has not been fully optimized, and currently invokes many per-row function calls. These branches limit its CPU efficiency.

We expect that our advantage over Parquet will eventually be eroded as the Parquet implementation continues to be optimized. Additionally, we expect that Parquet will perform better on disk-resident workloads as it issues large 8MB IO accesses, as opposed to the smaller page-level accesses performed by Kudu.

While the performance of Kudu compared with columnar formats warrants further investigation, it is clear that Kudu is able to achieve similar scan speeds to immutable storage while providing mutable characteristics.

$ 6.2 Comparison with Phoenix

Another implementation of SQL in the Hadoop ecosystem is Apache Phoenix[4]. Phoenix provides a SQL query layer on top of HBase. Although Phoenix is not primarily targeted at analytic workloads, we performed a small number of comparisons to illustrate the order-of-magnitude difference in performance between Kudu and HBase for scan-heavy analytic workloads.

To eliminate scalability effects and compare raw scan performance, we ran these comparisons on a smaller cluster, consisting of 9 worker nodes plus one master node, each with 48GB of RAM, 3 data disks, and dual 4-core Xeon L5630 processors at 2.13GHz. We used Phoenix 4.3 and HBase 1.0.

In this benchmark, we loaded the same TPC-H lineitem table (62GB in CSV format) into Phoenix using the provided CsvBulkLoadTool MapReduce job. We configured the Phoenix table to use 100 hash partitions, and created an equal number of tablets within Kudu. In both Kudu and Phoenix, we used the DOUBLE type for non-integer numeric columns, since Kudu does not currently support the DECIMAL type. We configured HBase with default block cache settings, resulting in 9.6GB of on-heap cache per server. Kudu was configured with only 1GB of in-process block cache, instead relying on the OS-based buffer cache to avoid physical disk IO. We used the default HBase table attributes provided by Phoenix: FAST DIFF encoding, no compression, and one historical version per cell. On Impala, we used a per-query option to disable runtime code generation in queries where it was not beneficial, eliminating a source of constant overhead unrelated to the storage engine.

After loading the data, we performed explicit major compactions to ensure 100% HDFS block locality, and ensured that the table’s regions (analogous to Kudu tablets) were equally spread across the 9 worker nodes. The 62GB data set expanded to approximately 570GB post-replication in HBase, whereas the data in Kudu was 227GB post-replication3. HBase region servers and Kudu tablet servers were allocated 24GB of RAM, and we ran each service alone in the cluster for its benchmark. We verified during both workloads that no hard disk reads were generated, to focus on CPU efficiency, though we project that on a disk-resident workload, Kudu will increase its performance edge due to its columnar layout and better storage efficiency.

| Q1 | scan 6 columns | [TPC-H Q1] |

|---|---|---|

| Q2 | scan no columns | SELECT COUNT(*) FROM lineitem; |

| Q3 | non-key predicate | SELECT COUNT(*) FROM lineitem WHERE l quantity = 48 |

| Q4 | key lookup | SELECT COUNT(*) FROM lineitem WHERE l orderkey = 2000 |

Table 2: Queries used to compare Impala-Kudu vs PhoenixHBase

| Load | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenix-HBase | 2152s* | 219 | 76 | 131 | 0.04s |

| Impala-Kudu | 1918s | 13.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.15s |

| Impala-Parquet | 155s | 9.3 | 1.4 | 1.5s | 1.37ss |

Table 3: Phoenix-HBase vs Impala-Kudu. Load time for Phoenix does not include the time required for a major compaction to ensure data locality, which required an additional 20 minutes to complete.

In order to focus on scan speed rather than join performance, we focused only on TPCH Q1, which reads only the lineitem table. We also ran several other simple queries, listed in Table 2, in order to quantify the performance difference between the Impala-Kudu system and the PhoenixHBase system on the same hardware. We ran each query 10 times and reported the median runtime. Across the analytic queries, Impala-Kudu outperformed Phoenix-HBase by between 16x and 187x. For short scans of primary key ranges, both Impala-Kudu and Phoenix-HBase returned sub-second results, with Phoenix winning out due to lower constant factors during query planning. The results are summarized in Table 3.

$ 6.3 Random access performance

3 In fact, our current implementation of CREATE TABLE AS SELECT does not enable dictionary compression. With this compression enabled, the Kudu table size is cut in half again.

4 git hash 1f8cc5abdcad206c37039d9fbaea7cbf76089b48

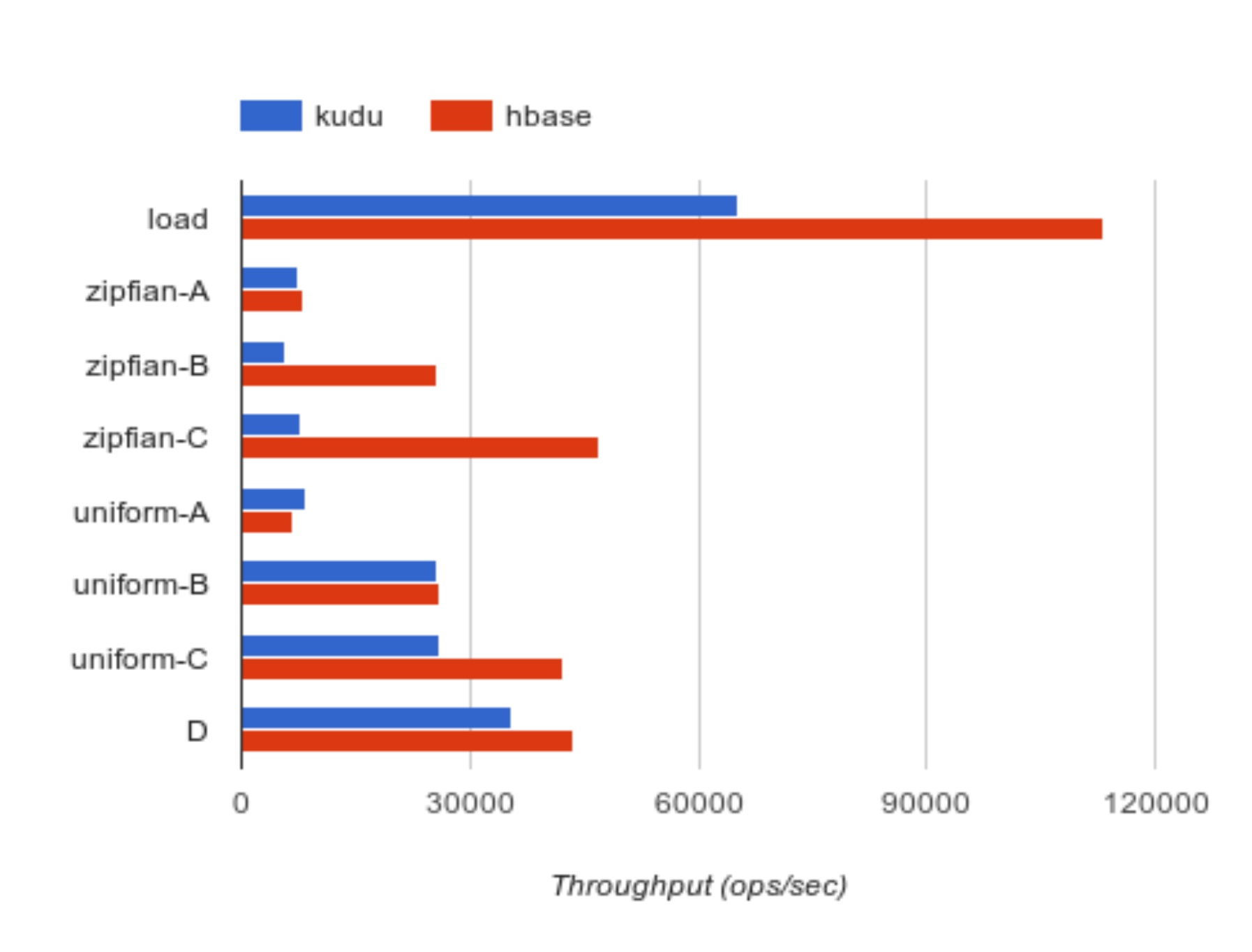

Although Kudu is not designed to be an OLTP store, one of its key goals is to be suitable for lighter random-access workloads. To evaluate Kudu’s random-access performance, we used the Yahoo Cloud Serving Benchmark (YCSB)[?] on the same 10-node cluster used in Section 6.2. We built YCSB from its master branch4 and added a binding to run against Kudu. For these benchmarks, we configured both Kudu and HBase to use up to 24 GB of RAM. HBase automatically allocated 9.6 GB for the block cache and the remainder of the heap for its in-memory stores. For Kudu, we allocated only 1GB for the block cache, preferring to rely on Linux buffer caching. We performed no other tuning. For both Kudu and HBase, we pre-split the table into 100 tablets or regions, and ensured that they were spread evenly across the nodes.

| Workload | Description |

|---|---|

| Load | Load the table |

| A | 50% random-read, 50% update |

| B | 95% random-read, 5% update |

| C | 100% random read |

| D | 95% random read, 5% insert |

Table 4: YCSB Workloads

the same 10-node cluster used in Section 6.2. We built YCSB from its master branch4 and added a binding to run against Kudu. For these benchmarks, we configured both Kudu and HBase to use up to 24 GB of RAM. HBase automatically allocated 9.6 GB for the block cache and the remainder of the heap for its in-memory stores. For Kudu, we allocated only 1GB for the block cache, preferring to rely on Linux buffer caching. We performed no other tuning. For both Kudu and HBase, we pre-split the table into 100 tablets or regions, and ensured that they were spread evenly across the nodes.

We configured YCSB to load a data set with 100 million rows, each row holding 10 data columns with 100 bytes each. Because Kudu does not have the concept of a special row key column, we added an explicit key column in the Kudu schema. For this benchmark, the data set fits entirely in RAM; in the future we hope to do further benchmarks on flash-resident or disk-resident workloads, but we assume that, given the increasing capacity of inexpensive RAM, most latency-sensitive online workloads will primarily fit in memory.

Results for the five YCSB workloads are summarized in Table 4. We ran the workloads in sequence by first loading the table with data, then running workloads A through D in that order, with no pause in between. Each workload ran for 10 million operations. For loading data, we used 16 client threads and enabled client-side buffering to send larger batches of data to the backend storage engines. For all other workloads, we used 64 client threads and disabled client-side buffering.

We ran this full sequence two times for each storage engine, deleting and reloading the table in between. In the second run, we substituted a uniform access distribution for workloads A through C instead of the default Zipfian (power-law) distribution. Workload D uses a special access distribution which inserts rows randomly, and random-reads those which have been recently inserted.

We did not run workload E, which performs short range scans, because the Kudu client currently lacks the ability to specify a limit on the number of rows returned. We did not run workload F, because it relies on an atomic compare-andswap primitive which Kudu does not yet support. When these features are added to Kudu, we plan to run these workloads as well.

Figure 1: Operation throughput of YCSB random-access workloads, comparing Kudu vs. HBase

Figure 1 presents the throughput reported by YCSB for each of the workloads. In nearly all workloads, HBase out-performs Kudu in terms of throughput. In particular, Kudu performs poorly in the Zipfian update workloads, where the CPU time spent in reads is dominated by applying long chains of mutations stored in delta stores 5. HBase, on the other hand, has long targeted this type of online workload and performs comparably in both access distributions.

Due to time limitations in preparing this paper for the first Kudu beta release, we do not have sufficient data to report on longer-running workloads, or to include a summary of latency percentiles. We anticipate updating this paper as results become available.

performs Kudu in terms of throughput. In particular, Kudu performs poorly in the Zipfian update workloads, where the CPU time spent in reads is dominated by applying long chains of mutations stored in delta stores 5. HBase, on the other hand, has long targeted this type of online workload and performs comparably in both access distributions.

Due to time limitations in preparing this paper for the first Kudu beta release, we do not have sufficient data to report on longer-running workloads, or to include a summary of latency percentiles. We anticipate updating this paper as results become available.

$ 7 Acknowledgements

5 We have identified several potential optimizations in this code path, tracked in KUDU − 749.

Kudu has benefited from many contributors outside of the authors of this paper. In particular, thanks to Chris Leroy, Binglin Chang, Guangxiang Du, Martin Grund, Eli Collins, Vladimir Feinberg, Alex Feinberg, Sarah Jelinek, Misty Stanley-Jones, Brock Noland, Michael Crutcher, Justin Erickson, and Nong Li.

$ References

[1] Apache Avro. http://avro.apache.org. [2] Apache HBase. http://hbase.apache.org. [3] Apache Parquet. http://parquet.apache.org. [4] Apache Phoenix. http://phoenix.apache.org.

[4] Apache Phoenix. http://phoenix.apache.org.

[5] LLVM. http://www.llvm.org.

[6] MongoDB. http://www.mongodb.org.

[7] Orcfile. https://cwiki.apache.org/confluence/display/Hive/LanguageManual+ORC.

[8] Riak. https://github.com/basho/riak.

[9] D. Abadi, D. Myers, D. DeWitt, and S. Madden. Materialization strategies in a column-oriented dbms. In Data Engineering, 2007. ICDE 2007. IEEE 23rd International Conference on, pages 466–475, April 2007.

[10] B. H. Bloom. Space/time trade-offs in hash coding with allowable errors. Commun. ACM, 13(7):422–426, July 1970.

[11] P. Boncz, M. Zukowski, and N. Nes. Monetdb/x100: Hyper-pipelining query execution. In In CIDR, 2005.

[12] F. Chang, J. Dean, S. Ghemawat, W. C. Hsieh, D. A. Wallach, M. Burrows, T. Chandra, A. Fikes, and R. E. Gruber. Bigtable: A distributed storage system for structured data. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst., 26(2):4:1–4:26, June 2008.

[13] D. Comer. Ubiquitous b-tree. ACM Comput. Surv., 11(2):121–137, June 1979.

[14] J. C. Corbett, J. Dean, M. Epstein, A. Fikes, C. Frost, J. J. Furman, S. Ghemawat, A. Gubarev, C. Heiser, P. Hochschild, W. Hsieh, S. Kanthak, E. Kogan, H. Li, A. Lloyd, S. Melnik, D. Mwaura, D. Nagle, S. Quinlan, R. Rao, L. Rolig, Y. Saito, M. Szymaniak, C. Taylor, R. Wang, and D. Woodford. Spanner: Google’s globallydistributed database. In Proceedings of the 10th USENIX Conference on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, OSDI’12, pages 251–264, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. USENIX Association.

[15] T. L. David Alves and V. Garg. Hybridtime accessible global consistency with high clock uncertainty. Technical report, UT Austin, Cloudera Inc., April 2014.

[16] J. Dean and L. A. Barroso. The tail at scale. Commun. ACM, 56(2):74–80, Feb. 2013.

[17] J. Dean and S. Ghemawat. Mapreduce: Simplified data processing on large clusters. Commun. ACM, 51(1):107– 113, Jan. 2008.

[18] S. Ghemawat, H. Gobioff, and S.-T. Leung. The google file system. SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev., 37(5):29–43, Oct. 2003.

[19] H. Howard, M. Schwarzkopf, A. Madhavapeddy, and J. Crowcroft. Raft refloated: Do we have consensus? SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev., 49(1):12–21, Jan. 2015.

[20] M. Kornacker, A. Behm, V. Bittorf, T. Bobrovytsky, C. Ching, A. Choi, J. Erickson, M. Grund, D. Hecht, M. Jacobs, I. Joshi, L. Kuff, D. Kumar, A. Leblang, N. Li, I. Pandis, H. Robinson, D. Rorke, S. Rus, J. Rus-sell, D. Tsirogiannis, S. Wanderman-Milne, and M. Yo-der. Impala: A modern, open-source SQL engine for Hadoop. In CIDR 2015, Seventh Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research, Asilomar, CA, USA, January 4-7, 2015, Online Proceedings. www.cidrdb.org, 2015.

[21] A. Lakshman and P. Malik. Cassandra: A decentralized structured storage system. SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev., 44(2):35–40, Apr. 2010.

[22] Y. Mao, E. Kohler, and R. T. Morris. Cache craftiness for fast multicore key-value storage. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM European Conference on Computer Systems, EuroSys ’12, pages 183–196, New York, NY, USA, 2012. ACM.

[23] K. Masui. Bitshuffle. https://github.com/kiyo-masui/bitshuffle.

[24] D. Ongaro. Consensus: Bridging Theory and Practice. PhD thesis, Stanford University, 2014.

[25] D. Ongaro and J. Ousterhout. In search of an understandable consensus algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2014 USENIX Conference on USENIX Annual Technical Conference, USENIX ATC’14, pages 305–320, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014. USENIX Association.

[26] R. Ramamurthy, D. J. DeWitt, and Q. Su. A case for fractured mirrors. The VLDB Journal, 12(2):89–101, Aug. 2003.

[27] K. Shvachko, H. Kuang, S. Radia, and R. Chansler. The Hadoop Distributed File System. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 26th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST), MSST ’10, pages 1–10, Washington, DC, USA, 2010. IEEE Computer Society.

[28] M. Zaharia, M. Chowdhury, M. J. Franklin, S. Shenker, and I. Stoica. Spark: Cluster computing with working sets. In Proceedings of the 2Nd USENIX Conference on Hot Topics in Cloud Computing, HotCloud’10, pages 10– 10, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010. USENIX Association.